Death Cleaning - The Art of Letting Go

I first heard about it while scrubbing away the stubborn food residue from my ceramic casserole dish. I was listening to AM TALK radio, which already gives you some idea of my age, when I heard coming up next, "Why you should try Death Cleaning!"

It turns out this new trend is less Marie Kondo and more Morticia Addams!

Death cleaning is based on a practice coined by Swedish author Margareta Magnusson and popularized in her book, "The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning."

The difference from Kondo’s joyful decluttering ritual is that in this Swedish approach, you are deciding how you can make your life more organized and less chaotic, not just for yourself but for those that will inherit your documents and possessions after, shall we say, you croak!

This practice of "death cleaning" is deeply rooted in the Swedish way of life and culture.

We know Swedes to be reserved, serious, and very practical-focused people. Hello IKEA! Who else would combine furniture shopping with cafeteria-style dining and delight over an inexpensive breakfast or Swedish meatballs?

This sensible practicality and perhaps a lack of sentimentality means the Swedes believe it is their duty to make life less complicated for those they leave behind by not burdening them with too many things to decipher after death.

Magnusson urges those 65 and older to start the process of shedding possessions. But of course, you do not have to wait until you are retired to start.

I dried off my favourite casserole dish, the one I took from Mom’s house after we emptied it when she passed, and it got me thinking about my situation.

When couples marry and start a family of their own, most times, prized possessions and things of sentimental value get passed on automatically to their children, whether they want them or not.

In my scenario, my husband and I do not have children, in which case my nieces and nephews would become the sole suckers, oops I mean beneficiaries.

I remember when my cherished parents passed away and my sister and I sifted through so many items, from furniture pieces to linens, dishes, clothes, and all the smaller souvenirs and miscellaneous things, that it was overwhelming. I connected every piece we touched to a memory, a smell, or an emotional current.

Giving things away felt like we were giving a piece of our family history away. And then I came across a document that struck me to my core with both sadness and shock.

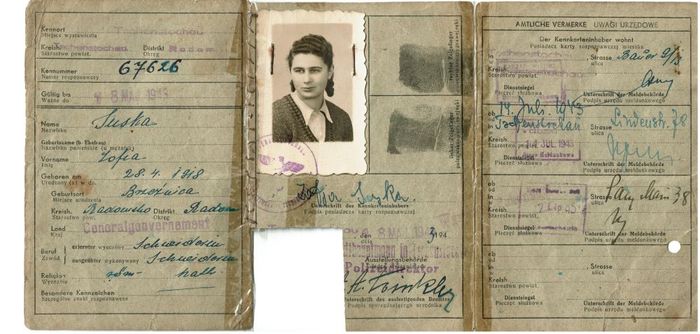

Hidden among a box of my parents' passports, insurance papers, and Canadian citizenship cards was my mom’s false identity, "Kennkarte."

A "Kennkarte" was an identity document issued in Nazi Germany that served as the basic identity document in the areas of the Third Reich.

My mom was a Holocaust survivor. Born in Czestochowa, Poland, this "kennkarte" had my mom’s photo but under a different name. Her miraculous survival is a tribute to her unrelentingly resilient nature, this false identity card, and I believe luck.

This past year, I reached out to the Montreal Holocaust Museum and underwent a formal application and approval process for the "transfer of property" of these precious items to the museum. My sister and I questioned whether it would be better to hold on to these and keep them in the family, but I felt strongly that they should be donated and preserved for educational purposes and future generations.

And so started my awakening about what possessions we hold on to that bring us joy and which items are just taking up space.

My mom enjoyed buying Nik Naks, or "tchotchkes," as we know them in Yiddish. The living room was a testament to her love of them and the dollar store conveniently located across her street.

It brought her happiness, she would say, to see something on every corner, end table, and surface. She would add that it gives her something to look at.

For some older adults, surrounding themselves with things and holding on to them may bring about a sense of comfort, security, and familiarity.

I am the complete opposite!

My preference is more minimal and serene in style, but as I look around the house, I see that my husband and I have managed to accumulate a lot of stuff.

The purpose of doing a Swedish death cleaning is not a morbid one; it is about having a conversation with your loved ones where honest communication is key.

Swedish death cleaning is also more than about disposing of possessions and parting with things willy-nilly; it is about taking inventory of your life.

It is not about planning for your eventual exit and who gets what, but about manifesting a more purposeful, simplified life where the emphasis remains on building connections and nurturing relationships over purchasing that next big gadget or material possession.

It is not about cleaning out your closet and reducing your clutter, but about living your best life authentically and realizing that by letting go of things, you might make room for personal growth, a sense of peace, and more meaningful and lasting sources of happiness and fulfillment.

Just don’t ask me to part with my mom’s casserole dish any time soon!

About the Author:

Wendy Reichental, B.A.,Dip. in Human Relations and Family Life Education, McGill University. Certified in Foot Reflexology, RCRT® Registered Canadian Reflexology Therapist.

Wendy enjoys capturing life’s passages in short essays and opinion pieces. Her writings have appeared in The Montreal Gazette, Ottawa’s Globe and Mail, and various online magazines. Wendy's unique take on those first days of the Pandemic lockdown is now part of the just-out anthology Chronicling the Days by Marianne Ackerman (Editor) and Linda M. Morra (Editor). Guernica Editions, Spring 2021